Fate

The only explanation I have is that fate brought me to Mongolia and this was the perfect place to start an adventure. Not because of the challenges overcoming language barriers and not being prepared for such a frigid climate but because of conversations last summer that were the catalyst to putting this plan in action.

Last summer while touring British Columbia by motorcycle, I began to understand the roots of why I enjoy travelling. I always just thought of it is as wanting to face new and unknown challenges but I began to realize I enjoy a variable state of change and seeing and learning about everything associated with the journey along the way.

On the way, I met Sabine when we both stepped off a bus in Port Renfrew, BC. We hiked the Juan de Fuca trail along the southwest coast of Vancouver Island together and she shared many intriguing stories of her almost two years of traveling the world by that point.

Sabine was often suggesting my expectations were wrong and that beginning to travel isn’t nearly as difficult as I imagined. While the easy explanation is to “blame” Sabine for inspiring all this, she was really only indirectly the reason for why I’m doing this.

It was a few weeks later when our paths crossed again in Jasper, Alberta to go canoeing across Maligne Lake. I had managed to secure a campsite and a canoe the day before after most bookings were cancelled due to the shitty weather forecast.

We had narrowly avoided being hailed on while canoeing across the lake but the rest of the night was very cold and wet. Then we sat with a couple from Edmonton under a rain shelter they had set up and, when they heard Sabine’s French accent, they drilled her on where she’s from and the places she’s been. It was this conversation that led me to this point.

The couple and Sabine had both followed similar routes through central Asia and they were comparing stories. Without having done anything remotely similar, all I could really do was sit there and absorb. The part that I was most fascinated by was their incredible experiences with nomad families in Mongolia. It all sounded so surreal and unbelievable because all I’ve ever experienced is the western world.

I didn’t think much of it at the time but a week later I kept dwelling on not the stories but us all sitting there in silence afterwards and seeing the intense look of satisfaction on those three faces as they reflected on those experiences and I had never been so envious in my life.

I spent the following week working in nearby Hinton and I was getting very little sleep in the series of shitty motels that were the only availabilities the office managed to find. My restless mind was left to wander, thinking about the logistics of actually pulling off something I had been thinking about. Alberta and BC still have plenty of adventures to offer but I wanted to step so far outside that box that the box no longer existed. In those late hours lying awake in uncomfortable motel beds, I fired up Excel and started crunching some numbers and things started to actually make sense. The impossible idea that lay deeply buried in my mind started to emerge as remotely possible and the momentum continued from there.

I was planning another roughly week-long hike in Jasper National Park starting in September but, after speaking with the park office, I lost interest in that plan. Landslides and forest fires meant the trail was 75km shorter and the trailheads were now 300km apart so it became more challenging but not for the right reasons.

Instead, I asked Sabine if she’d be willing to meet up again in Mexico. All I told her was that I needed her help putting a plan in action that would be impossible for me to do alone and I thought she had the experience, and more importantly, a similar mindset needed to pull it off. I slowly fed her a series of extremely vague, if not misleading, clues over the coming weeks to build anticipation and intrigue. It may have been a little devious but that anticipation was more intentionally for my own benefit to make sure I stayed focused and didn’t cave to common sense.

Several days after arriving in Mexico, I shared the full details of my plan to Sabine and handed her a prepaid credit card so I would not know the amount needed to make it a reality. Not wanting to be even remotely responsible if things went wrong but also curious of the outcome, Sabine reluctantly agreed to help. I had already established a few guidelines and precautions and emphasized how the destination must remain a secret, especially from me until I arrived there.

This idea seemed logically impossible, even if I didn’t know before the first flight. In a modern society where everything is tracked and presented to you at multiple steps along the way, it seemed like just a matter of time before the name of the destination country would slip through the cracks.

Two days before we parted ways in Guatemala, we had been talking about potential countries I’d like to visit. Sabine asked me about Mongolia but she didn’t think it could qualify. She was surprised when I told her Canadians are allowed Visa-free entry into Mongolia so it did in fact qualify as a potential destination if the dart landed there. However, I had somewhat forgotten about the conversations a month prior so all I remembered about Mongolia is there being desert and camels so it seemed like it would be a great place to end up.

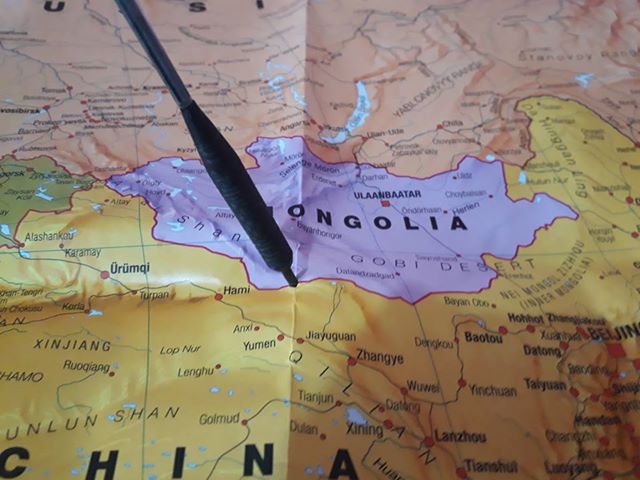

The next day, I finally threw the dart at the map. It took five or six attempts and, to ensure a completely random destination, the map was rotated between throw and I was blindfolded when I threw the dart backwards while facing away from the map. The first time the dart hit the bed-sized map, it landed in the center of Greenland.

Since there’s nothing there but hundreds of kilometers of ice, Sabine asked me to throw again. Obviously, the next time the dart landed wasn’t much better but she felt is was remotely possible.

I don’t recall exactly what I asked Sabine immediately after that last throw but as she stumbled over her words to come up with a reply that wouldn’t be revealing, she said “Well… I’d like to!” When I was handed the customs form on my final flight and read the name “Mongolia” I immediately realized that I had completely misinterpreted her response.

To me, it strongly implied that the destination was a country she had not yet been to. I had already known Mongolia was a country she had visited so I was not at all expecting to see that country on the customs form. At the time, I had no idea her response really meant Mongolia would be a place she’d like to revisit during the winter to see the contrast from when she visited in the summer.

Perhaps it was Sabine being misleading to get back at me for being so devious and misleading when revealing clues to my plan but it was just

the type of deception I needed to not suspect Mongolia as a potential destination.

Aside from getting Sabine’s help with the plan, the three weeks I spent in Mexico, Guatemala, and Belize were to get my feet wet in international backpacking. I asked very few details or tips from Sabine because I intentionally wanted to begin this journey with very little expectations or preparation and wandering back to Mexico from Guatemala took just long enough to get a very rough idea if what is to come is really something I can handle and to test out my gear in a tropical climate for the first time.

What most people don’t know is that there was a second part to my initial plan. Survival challenges are exciting to me but I wanted to try something very different. I wanted to attempt more of an urban survival challenge once I reached the destination and I was intending to seek out and rely entirely on the generosity of others to survive the first week. The main reason for this was as a way to force myself outside the bubble I live in. I’m fully aware I live a sheltered life so I wanted to do something so opposite to my boundaries of comfort that I’d have no choice but to break free, adapt, and embrace the nuances and quirks the world has to offer.

I failed that second goal but I’m ok with that. In theory,

Mongolia would be the ideal place to succeed at a survival challenge like this. Nomad hospitality is dependable but I was not expecting a language barrier to be the impassible wall. Not having enough room in my pack for additional puffy layers to cope with the climate also made camping in the desert in January impossible.

Reflecting on it now, I suppose I actually did succeed but it was a few weeks later and, probably for the better, long after I had given up on the idea so I had completely different intentions by that point.

Honestly, I really disliked the first few days and I was beginning to wonder if maybe I made a huge mistake. The Mongolian language has a very different pronunciation. All Mongolian language translation apps required Internet connectivity to function and dictionary apps only translated into Cyrillic which I also can’t read. I saw a sign on the side of a gas station in Dalanzadgad that said “GMobile” so I tried to buy a sim card for my phone. To my complete surprise, the lady actually understood a tiny bit of English. She was then able to get me in touch with another couple that was willing to take me on a tour of the south Gobi desert to get a bit closer to where the dart ultimately landed, in a very remote area of the Gobi desert along the border with China.

Being low season when tourism is mostly shut down for the winter, my driver and guide, Baatar, had just one foreigner go on a tour a couple months prior so he was more than willing to get off the couch and take me out into the desert.

While the three day tour was an eye-opening experience, I wasn’t satisfied. My guide learned to speak English just from driving tourists into the desert in the summer but it wasn’t enough to carry on a conversation. While visiting and staying with nomad families, my guide rarely translated anything so I felt so awkward. All I could really do was sit there like a video camera and silently watch these families live their lives. I felt like such a tourist and that annoyed me. My guide and his wife later offered multiple other options, all of which I declined to try to find a better way of immersing myself in the Mongolian culture. I wanted to feel like a part of it, not just a witness to it.

I left Dalanzagad and headed back to Ulanbaataar where there was a better potential for finding an English speaking guide. It took a couple weeks but Dashka, a manager of the Sunpath hostel in Ulanbaataar very generously agreed to let me go stay with him and his nomad parents for almost three weeks and be my translator because his parents didn’t speak any English. I didn’t know it at the time but Mongolian Immigration informed me there was no way to extend my stay beyond 30 days. Extensions only apply to visas and, since I had a visa-free entry, there was nothing to extend. I couldn’t apply for a Mongolian visa without first leaving the country so that meant I could only stay with Dashka’s nomad family for a week before leaving the country.

While it was only a week, this experience was exactly what I was seeking and it ended up being so much more rewarding of a life experience than I imagined while sitting envious at that picnic table in the rain several months prior. I now understand that look of satisfaction on their faces and I hope I can continue to develop experiences as rich as this one throughout this journey.

So far… no regrets